Explore Heritage Hall

Fur Trader’s Cabin

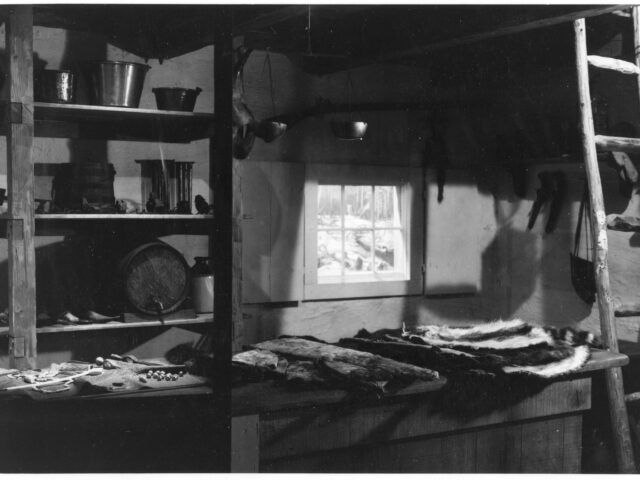

The Fur Trader’s Cabin is a real cabin built around 1830 on Grand Island, Michigan and used as a fur trading post. People, including Native American and white trappers, brought furs (such as beaver, bear, and otter) to exchange for goods like tools, pots, cloth, and blankets. When the fur trade declined in the area in the 1840s, the cabin was used for other purposes. In 1965, the cabin was donated to the MSU Museum and reassembled inside Heritage Hall. Today, the cabin is set up to represent a fur trade cabin from the 1780s on the Grand River near the Lansing area. It displays tools, materials, furs and other typical objects found in a fur trade cabin from this time period.

Fur trading in North America was a complex international system, including indigenous people and Europeans, that had long lasting political, economic, cultural, social, and environmental impacts. Exhibits like this cabin can only portray certain aspects of that system. People involved in the fur trade were part of an international network to provide raw materials (furs) for making hats and clothing. Demand for raw materials to make products is a part of our daily lives. How might the Fur Trader’s Cabin help us think about product systems we are part of today?

Publishing and Printing Shop

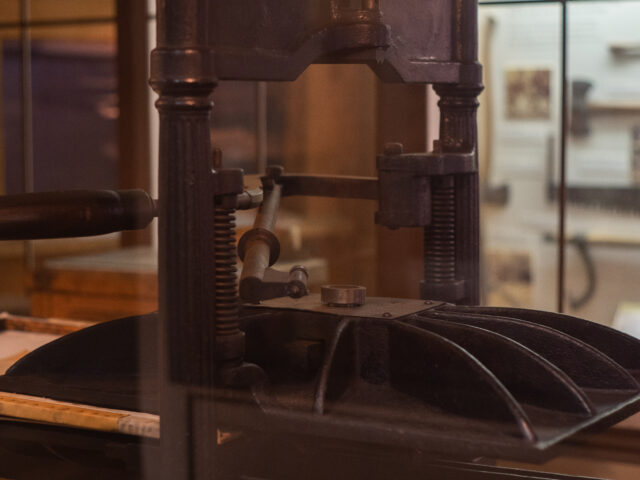

Sharing information has always been important in communities. The “Printing Shop” represents how people published and printed information in the 1890s. Although the outside of the building is a recreation and not an original building, inside is a R. Hoe & Company Washington printing press (probably manufactured in the 1860s or 70s), examples of printed matter, and tools and supplies necessary for printing. A shop like this would have made cards, letterhead, and other paper items needed by businesses and community members.

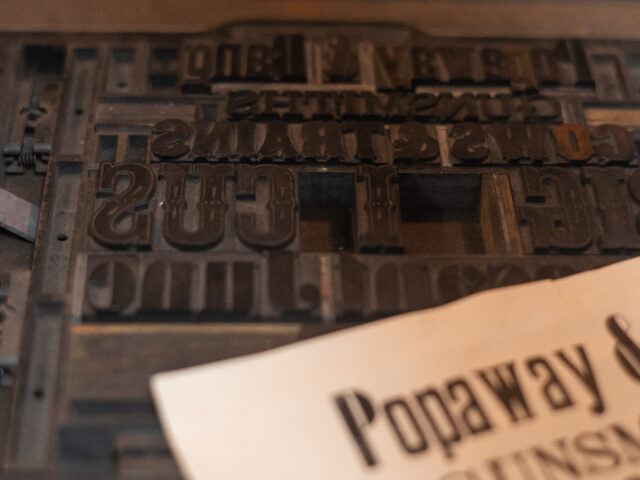

Printing in the 19th-century was very different than today. Printers used moveable type: individual letters that were assembled into words and then lines of text. Type was set into a frame the size of the page to be printed. Ink was spread over the type and the paper placed over that. When the press was pushed down, the ink transferred to the paper, and the letters printed. From this process, one sheet was printed. Can you imagine how time consuming this was compared with writing on a computer and clicking “print” today? How much does communication today rely on the printed page?

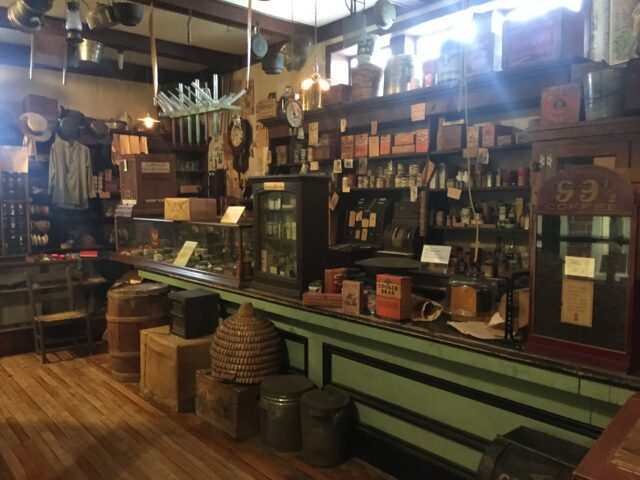

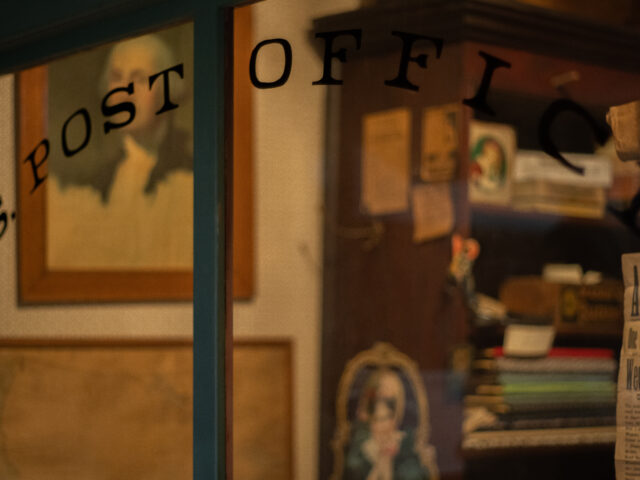

Crossroads General Store

This exhibit shows how people shopped in a rural Michigan town from the 1880s-1920s. It displays groceries, candy, mail, hardware, medicine, and other objects sold in a typical general store at that time. While the outside of the building is a recreation, many fixtures and items on display are from the Rykala General Store in East Lake, Michigan (donated by the Rykala family in 1963).

Like our stores today, general stores carried foods and items that local people did not make, grow, or harvest themselves, such as clothing, hardware, and medicines. Most food items in the late 1800s were sold in bulk or without packaging. In the early 1900s, packaged food items became more common. Many items at the store were not self-service like today. The store owner or clerk would get packages off shelves and weigh/wrap bulk items for customers. General stores also provided community gathering space for people, to get mail, hear news, and talk to neighbors. Although how we shop has changed, the need to shop is still the same. How are your shopping experiences different today?

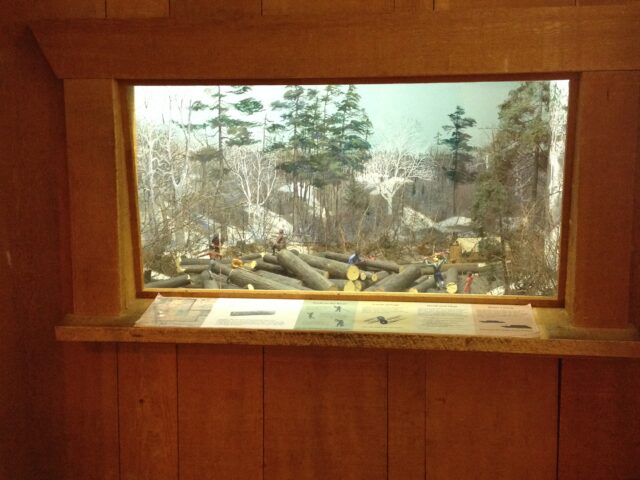

White Pines and Peavies

Lumbering was big business in Michigan in the 19th century. Towering trees were harvested and floated down Michigan’s rivers from the forests to the lumber mills. When the ice melted on the rivers in early spring, the log drives began – day and night until September. A long, metal-tipped stick called a pike pole pushed logs in the right direction. If a logjam happened, a peavey with its swinging hook provided great prying power for moving logs. If this didn’t work, the foreman might use dynamite to do the job! Both of these tools are on display in the exhibit.

Loggers stamped marks on log ends to identify the owners. Often logs of different owners became mixed together. River drivers put logs with different marks in large “booms” or log corrals to be sorted later. Crews worked in 12-hour shifts, 100 men per crew. The work was dangerous, wet, and cold. Women also worked in camps or nearby, cooking and providing laundry services.

How to Build a Fur Trader’s Cabin

Ever wonder how to build a cabin? How about the Fur Trader’s Cabin exhibit at the MSU Museum? It’s a real cabin that was built around 1830 on Grand Island, Michigan. Abraham Williams came to the island with his family in 1840 to operate the fur trading post. Anna Marie Williams (later Powell), his daughter, remembered that summer day:

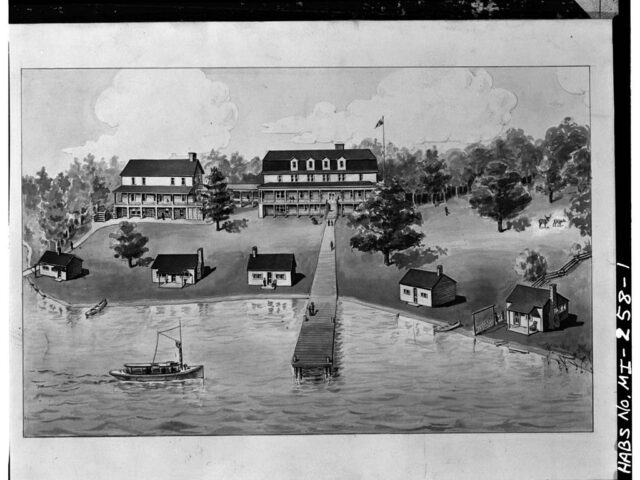

“I’ll never forget how the Island looked the first time I saw it. I was twelve. Quite a big girl. I’d learned to knit double and twisted… We came to the Island in the schooner Mary Elizabeth. It took us two weeks from the Sault… We landed on the mainland July 30, 1840. They had told father at the Sault that the buildings at the trading post were habitable. There were four log-houses. The biggest one had been used as a store. It had counters and shelves.”*

When the fur trade declined in the area, the cabins were used for other purposes. New buildings were added to the site, including the big Hotel Williams. (The Museum’s cabin in second from the left along the shoreline in this old drawing.) In 1965, the property owner, the Cleveland Cliffs Mining Company, decided to remove the cabins. One cabin was donated to the MSU Museum. The building was taken apart and each piece carefully numbered, so it could be put back together the right way at the Museum. All the pieces were loaded onto a big truck, driven to East Lansing, and reassembled (with a few changes) inside Heritage Hall. Some parts, like the chimney and roof, are not original.

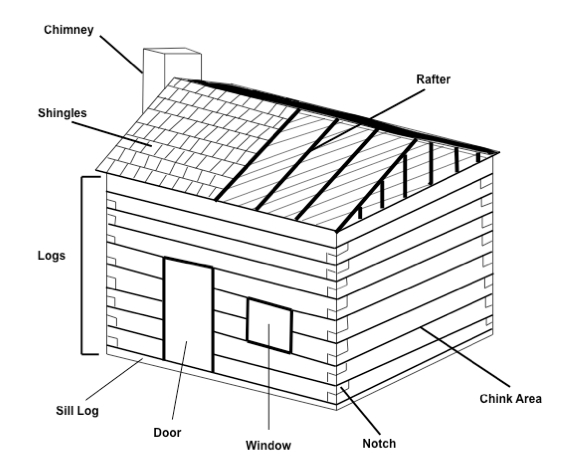

What pieces do you need to build a cabin?

THE MAIN PARTS – STARTING AT THE BOTTOM AND BUILDING UP!

Sill log – The first, bottom (foundation) log of a cabin wall. This log supports all the others. Because these logs sit right on the ground, they often rot away from moisture damage.

Logs – Logs are stacked on top of each other to form the walls. The bark may be peeled off or left on.

Notch – A special cut made on the end of a log. There are different kinds of notches, but they all work to lock the logs of a cabin together.

Chink area – Space between the logs. This space is filled with a material to keep out the weather. In the past, people used a plaster-like mud called daub, which became hard when it dried.

Rafter – Wooden beam that holds up the roof of a building. The rafters are usually covered with pieces of wood to which the shingles are nailed.

Shingles – Pieces of wood or other material that are used to cover a roof. They are nailed to the wood covering the rafters. Shingles help to keep out rain and snow.

OTHER PARTS

Door – To get in and out of the cabin

Window – To let in light. In the past, many cabins would not have had glass windows, since glass was very expensive and hard to transport without breaking.

Chimney – A structure attached to a fireplace and used to vent smoke out of a building. Usually made of stone or brick.

Learn More

National Park Service Preservation Brief 26: The Preservation and Repair of Historic Log Buildings

*Beatrice Hanscom Castle, The Grand Island Story (Marquette, MI: John M. Longyear Research Library, 1974) 31-32.